There’s One Fix for Fake News – Name Every Source

Here’s a bolder solution: ban the blind quote. If a statement can’t be backed by a named source or verifiable public record, it doesn’t make the news.

Every anonymous whisper is an invitation to misinformation.

News consumers today are drowning in hearsay and propaganda masquerading as fact – and it’s costing us dearly. Trust in the media has plummeted to record lows (only 31% of Americans express confidence that news is reported fully and fairly), while the global price tag of false information tops $78b each year. From stock markets briefly losing $136b on a single fake tweet to millions of people making bad decisions based on online hoaxes, the stakes could not be higher. We’ve tried half-measures and tech fixes. Here’s a bolder solution: ban the blind quote. If a statement can’t be backed by a named source or verifiable public record, it doesn’t make the news.

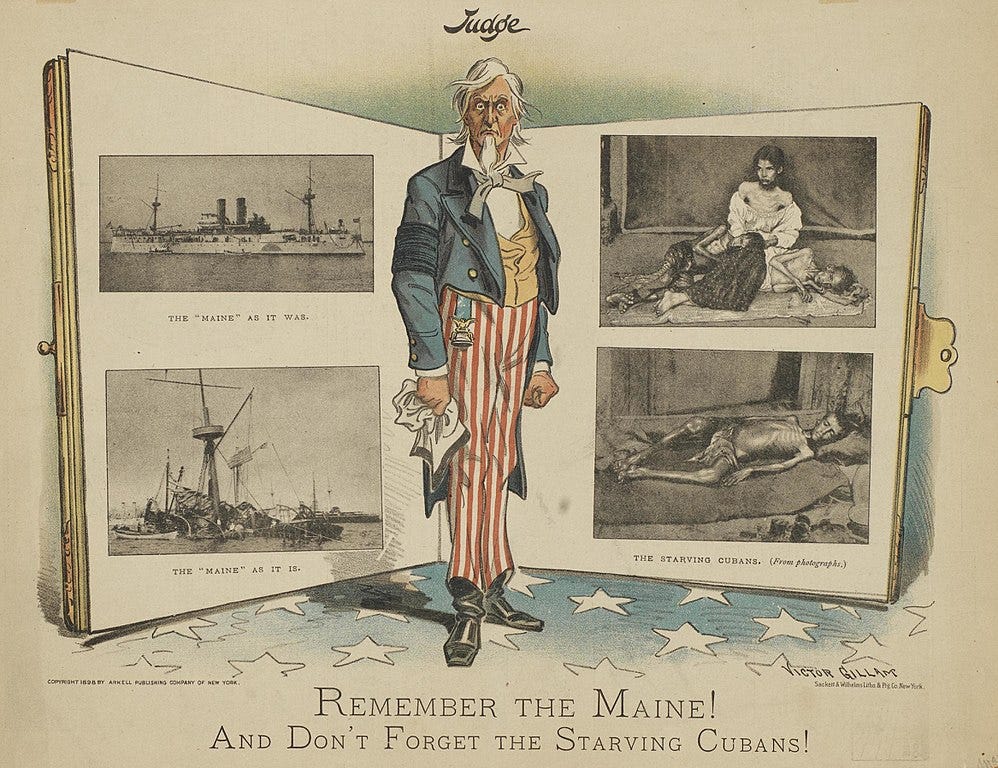

Yellow Journalism is a red flag.

Misinformation is nothing new – over a century ago, it literally helped start a war. Reading this actually triggered me to write this article.

In 1898, the U.S. battleship Maine mysteriously exploded in Havana Harbor. Hearst’s and Pulitzer’s rival newspapers rushed to blame Spain without evidence, splashing “Remember the Maine!” across front pages and whipping the public into a war frenzy. It worked: the Spanish–American War followed, with Congress and President McKinley pressured by a media-induced outcry. The truth (that the explosion’s cause was never proven) mattered less than the sensational narrative – and hundreds of thousands paid the price in a war at least partly enabled by “fake news”. Reading this made me draw obvious parallels - but that’s not where I am focusing my argument.

Digging deeper, the links of this pattern are everywhere - and it’s littered history.

The Brits did it in 1924 and published a forged letter (the Zinoviev letter) from some Soviet leader urging revolution - leading to the Labour government losing an election - only to then be revealed as a hoax.

In the US, Rolling Stone did it in 2014 about supposed campus crimes - all based on one anonymous source.

Each episode underscores a pattern: when journalists bypass normal verification in favour of unvetted claims, the consequences can be dramatic and dire.

A Costly Epidemic of Unverified Claims

Today’s information ecosystem turbocharges those risks. With social media and 24/7 news, rumours can go global in minutes – and they do real damage.

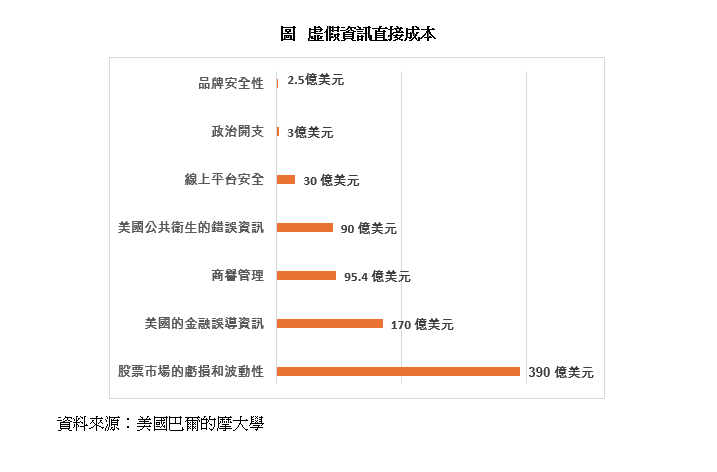

A 2019 study, by Professor Roberto Cavazos at the University of Baltimore, quantified how fake news now causes $39b in annual stock market losses and another $17b in misguided investment decisions. Companies spend over $9b a year combating phony rumours about their brands. And it’s not just money: misinformation about health (think anti-vaccine conspiracy theories) costs lives and so many billions in public health setbacks. The World Economic Forum bluntly ranks disinformation as a top global threat.

Worst of all is the damage to trust itself. A news industry that once enjoyed broad credibility now finds more people have no trust at all in it (36% in the US) than a great deal of trust. One major culprit is the media’s reliance on unnamed sources that readers can neither verify nor hold accountable.

As one editor notes, anonymous posts can destroy reputations and erode media credibility – when outlets echo shadowy claims without evidence, “we risk becoming part of the problem”.

In one Pew survey, 26% of journalists admitted they had unknowingly reported a story that turned out to be misinformation. That should be a sobering wake-up call.

"From Our Source…” said the very serious journalist. This is an original sin.

Journalists often defend the use of unnamed sources by citing historic wins – the Pentagon Papers, Watergate’s “Deep Throat”, etc. Indeed, anonymity can occasionally enable whistleblowers to expose corruption or wrongdoing. But those should be the rare exceptions. Far more often, shielding a source’s identity hides agendas and invites falsehoods with no repercussions.

Consider the run-up to the 2003 Iraq War: major U.S. outlets printed sensational claims about WMDs based on “senior officials” who insisted on anonymity – claims that turned out utterly wrong. One New York Times reporter (Judith Miller) relied on a parade of unnamed administration sources and an Iraqi defector with a fake name in her WMD stories. The result? A national delusion of secret weapons, a war launched on false pretenses, and that reporter’s eventual disgrace when her claims “were later discovered to have been based on fabricated intelligence”. The lesson: if your story can’t survive without anonymous assertions, maybe it shouldn’t be published at all.

Look at how quickly anonymity can backfire. The Rolling Stone case in 2014 wasn’t just a bad article; it became a cultural flashpoint showing how one unverified source can mislead millions. In Canada, where libel laws are stricter, a news outlet that prints a defamatory claim from an unnamed source can be sued out of existence if it can’t prove the allegation true. Unnamed sources “muddy the water” legally and ethically. As veteran editors stress, journalism is about accountability. If someone isn’t willing to put their name to an accusation, should journalists really broadcast it to the world? In an age where any liar with a keyboard can start a viral lie, the last thing the news industry needs is to echo the opaque and unverifiable.

Blurred Lines and Hidden Agendas

The problem isn’t just faceless “sources” in text – it’s also public figures playing double roles under cover of ambiguity. Take David Sacks, a Silicon Valley investor turned White House adviser. Upon accepting the role of AI and crypto czar, Sacks initially hinted he’d step back from public punditry to avoid conflicts. He even dialled down his presence on his own popular podcast (All-In) when topics neared his government turf.

But as months passed, that resolve melted away. Now he freely opines on all manner of policy on-air, even as he continues to invest in tech startups that could profit from the very regulations he’s helping shape. Sacks secured not one but two ethics waivers to keep his private venture interests while in public office – a legally blessed conflict of interest that one ethics professor bluntly called “graft… letting [Sacks] make money while insulating him from criminal liability”.

This blurred line between public duty and private gain thrives in shadows. If journalists cover such figures, they must shine an unforgiving light. That means pressing for on-the-record comments and documented proof of claims.

No “a source close to Sacks says he divested quietly” – show us the 11-page ethics waiver itself (yes, it’s public). And when Sacks or others make assertions, demand the receipts. In one case, Sacks insisted he’d sold his crypto to avoid even the “appearance of a conflict”; well, reporters obtained the actual waiver and found it never revealed the dollar amounts, just percentages. Only by scrutinising the primary documents did the truth emerge: even a “mere 3.8%” stake for a billionaire can mean tens of millions at risk. That kind of fact-checking is journalism’s job – and it can’t be done if we accept vague assurances from unnamed contacts.

No more off the record.

It’s time to break the cycle. Journalists must abandon the crutch of anonymous sourcing except in the most extreme circumstances (genuine whistleblower peril, for example, and even then an editor must know the name ). This is admittedly a radical shift. Yes, some important information may never come to light if we make this change – some leakers will stay silent rather than be named. Yes, it puts more pressure on organisations to strengthen whistleblower protections so insiders can safely come forward on the record. But think of the upside: a world where every quote you read in the news is attached to a name, a face, and accountability. No more “sources say” political hit jobs; no more policy rumours based on some staffer’s agenda; no more doubt about whether a journalist just made it up. Every claim would carry the weight of evidence or attribution, or it wouldn’t be printed at all.

Ironically, even the tech platforms accused of fuelling misinformation are flirting with the value of verified facts. On X (formerly Twitter), millions of users have started tagging @Grok, to instantly fact-check dubious posts in real time. The idea of a “truth bot” at everyone’s fingertips is intriguing – and the public appetite for quick verification is clearly there. Grok’s execution, however, has been shaky. In one case it confidently misidentified a viral photo and had to correct itself hours later. In another, both Grok and ChatGPT wrongly “fact-checked” a genuine image as fake, causing a cacophony of confusion before human fact-checkers set the record straight.

The lesson from AI: technology can assist, but it can also amplify errors at scale. Ultimately, there’s no substitute for rigorous editorial standards set by humans. If anything, these AI misfires reinforce the need for journalists to model accuracy – by refusing to publish what they haven’t verified.

Some editors worry that “no anonymous sources, ever” is too absolutist. But consider the alternative. We continue as-is, and each high-profile mistake (from UVA to WMDs to whatever’s next) chips away at media credibility until nothing’s left. News organisations become just another noise in the disinformation bazaar. Or we draw a line: no name, no quote. The truth in print would then be backed by people willing to stand behind it – or by hard evidence accessible to all (documents, data, recordings). That might shrink the universe of stories a bit, but those we do get would be far more bulletproof. It would also force sources with genuine concerns to channel them through legal whistleblower routes, official reports, or press conferences where they can be questioned. Yes, power abusers will find it harder to be exposed. That’s a trade-off society will have to navigate with stronger whistleblower laws and perhaps confidential ombudsmen. But continuing to rely on backroom quotes in the “from my sources” tradition is clearly not solving the problem – it’s part of the problem.

In the end, fighting misinformation isn’t just about debunking falsehoods after they spread; it’s about choking off their supply. By eliminating anonymous assertions from reputable journalism, we slam one major door that falsehoods have strolled through for decades. Sure, politicians and execs will grumble (“We can’t give you the scoop if you won’t protect us!”). Let them. Newsrooms will endure some dry spells as they adjust. But over time, a funny thing might happen: readers will start to believe again. Each sentence in a report, having a transparent source, will feel more trustworthy. The fringe “ghettos of information” – those conspiracy-laden corners of the internet – will have a harder time competing with verifiable reality. Platforms might even pivot from amplifying rage-bait to elevating content with concrete sources, knowing that’s what informed users demand.

Strip away the shadows, and truth has a fighting chance. It boils down to a simple ethos: If you can’t say it on the record, don’t expect to see it in print. That one change would upend decades of journalistic convention. But it would also place journalism back on the side of enlightenment values – evidence over intrigue, light over darkness. In an information war currently being lost to lies, this is how we raise the cost of deception. Public figures would know that to get their narrative out, they must attach their name and reputation to it. And anonymous trolls? They’d have no newspaper megaphones left to hide behind.

It won’t be easy. Old habits and scoop incentives die hard. Yet doing nothing is clearly harder in the long run – on our democracy, our economy, and our sanity. The media’s one key rule for the new era should be the exact opposite of its old one: Sunshine isn’t just the best disinfectant; it’s now the only credible source. No name, no news. Period.

References

Brenan, M. Gallup, 2024 – Americans’ Trust in Media Remains at Trend Low.

Tse, M. & Ho, C. HKU Business School, 2024 – Combat Misinformation for a Stable Economy.

Serrano, J. World Economic Forum, 2025 – The real cost of disinformation for corporations.

Woolf, C. PRX The World, 2016 – Back in the 1890s, fake news helped start a war.

McDonald, L. Pique Newsmagazine, 2025 – Why anonymity in journalism should be the exception.

Loizos, C. TechCrunch, 2025 – David Sacks and the blurred lines of government service.

Al Jazeera, 2025 – As millions adopt Grok to fact-check, misinformation abounds.

Buttry, S. (via Landay) The Buttry Diary, 2015 – Critique of Judith Miller’s WMD reporting.